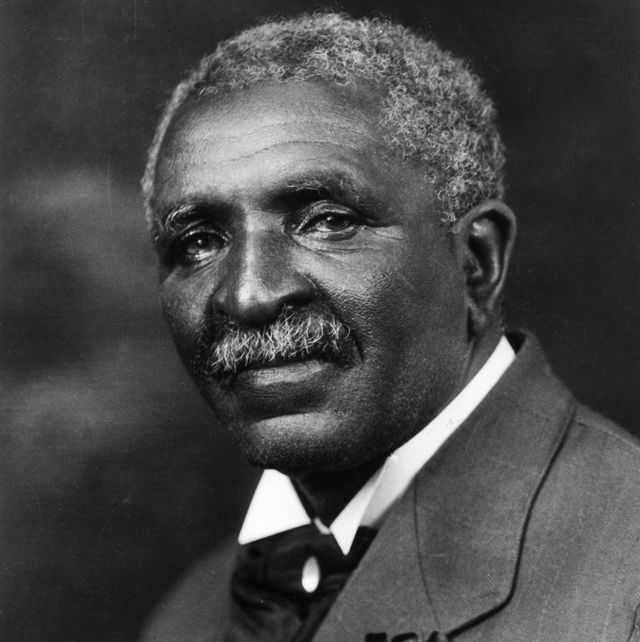

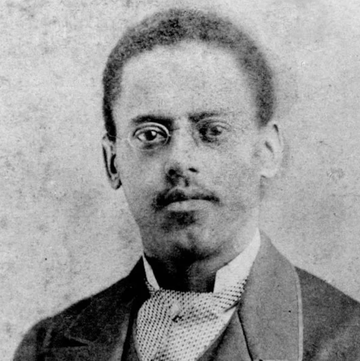

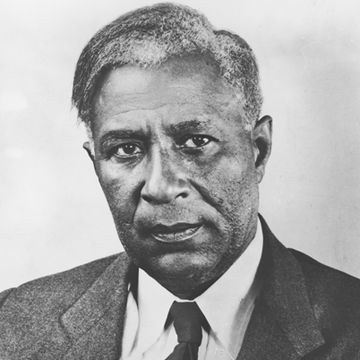

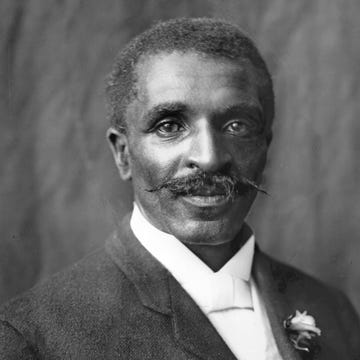

c. 1864-1943

Who Was George Washington Carver?

George Washington Carver was a Black scientist and inventor famous for his work with the peanut; he invented more than 300 products involving the crop, including dyes, plastics, and gasoline, but not peanut butter. Born enslaved, Carver developed an interest in botany and eventually earned a master’s degree from the Iowa State Agricultural College (now Iowa State University). He became a longtime teacher at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, an advocate for farmers, and an internationally renowned botanist who consulted for President Theodore Roosevelt and Indian leader Mahatma Gandhi. Carver died in 1943 around age 78 and became the first African American to have a national monument created in his honor.

Quick Facts

FULL NAME: George W. Carver

BORN: c. 1864

DIED: January 5, 1943

BIRTHPLACE: Diamond, Missouri

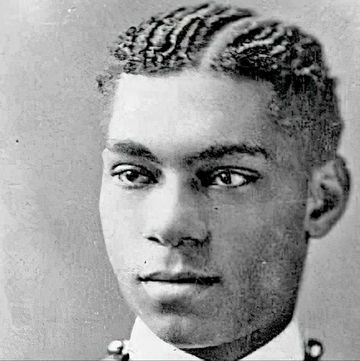

Early Life: When Was George Washington Carver Born?

George Washington Carver was most likely born in 1864 in Diamond, Missouri, during the Civil War years. Like many children of slaves, the exact year and date of his birth are unknown. He was one of many children born to Mary and Giles, an enslaved couple owned by Moses Carver. Giles died in an accident prior to his son’s arrival.

A week after his birth, George was kidnapped from the Carver farm, along with his sister and mother, by raiders from the neighboring state of Arkansas. The three were later sold in Kentucky. Among them, only the infant George was located by an agent of Moses Carver and returned to Missouri.

The conclusion of the Civil War in 1865 brought the end of slavery in Missouri. Moses and and his wife, Susan, subsequently raised George, as well as his older brother James, and gave him their surname.

In his later recollections, George described himself as a sickly child whose body was feeble and in “a constant warfare between life and death to see who would gain the mastery.” As a result, he often assisted Susan with domestic chores instead of doing farm labor and learned how to cook and embroider.

While living there, George developed a fascination with plants and collected specimens from the nearby woods—a hobby that foreshadowed his accomplishments later in life.

Education

Because no local school accepted Black students at the time, Carver’s stand-in mother, Susan, taught him to read and write. The search for knowledge remained a driving force for the rest of George’s life.

When he was around 11 to 12 years old, he left the Carver home to travel to a school for Black children about 10 miles away in the town of Neosho. Although George never lived on the Carver farm again, he kept in touch with Moses and Susan and often returned to visit them.

While at school in Neosho, Carver lived with Mariah and Andrew Watkins, a Black couple who offered him lodging in exchange for help with household tasks such as laundry. Upon meeting Mariah, the boy introduced himself as “Carver’s George,” as he had done his whole life in reference to his prior owner and caretaker. Mariah told him from now on he should refer to himself as “George Carver.”

Years later, Carver adopted the middle initial “W” to distinguish himself from another man named George Carver, but it didn’t stand for any name in particular. A reporter once asked him if the initial stood for “Washington,” and he replied, “Why not?” However, Carver never actually used the name Washington and signed letters as simply George Carver or George W. Carver.

Mariah was a great influence for Carver, introducing him to the African Methodist Episcopal Church and encouraging his studious habits. “You must learn all you can, then go back out into the world and give your learning back to the people,” she told him.

Carver attended a series of schools before receiving his diploma at Minneapolis High School in Minneapolis, Kansas. Initially accepted to Highland College in Highland, Kansas, Carver was later denied admittance once college administrators learned of his race. Instead of attending classes, he homesteaded a claim, where he conducted biological experiments and compiled a geological collection.

While interested in science, Carver was also interested in the arts. In 1890, he began studying art and music at Simpson College in Iowa, developing his painting and drawing skills through sketches of botanical samples. His obvious aptitude for drawing the natural world prompted a teacher to suggest that Carver enroll in the botany program at the Iowa State Agricultural College (now Iowa State University).

Carver moved to Ames and began his botanical studies the following year as the first Black student at Iowa State. He excelled in his studies. Upon completion of his bachelor of science degree in 1894, Carver’s professors Joseph Budd and Louis Pammel persuaded him to stay on for a master’s degree, which he completed in 1896.

His graduate studies included intensive work in plant pathology at the Iowa Experiment Station. In these years, Carver established his reputation as a brilliant botanist and began the work he pursued throughout his career.

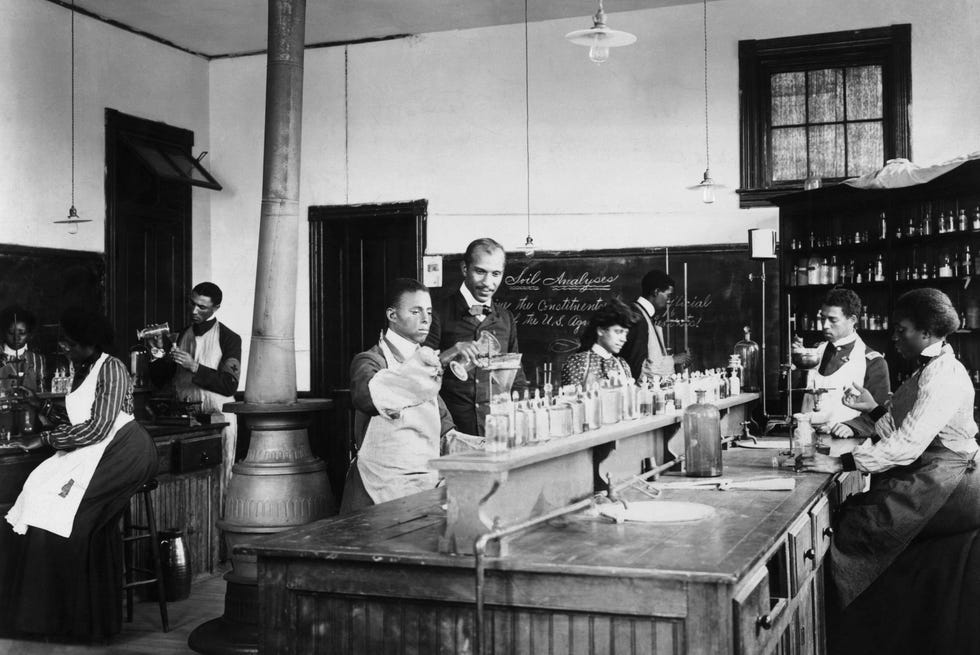

Tuskegee Institute Teacher

After graduating from Iowa State, Carver embarked on a career of teaching and research. Booker T. Washington, the founder of the Tuskegee Institute, hired Carver to run the historically Black school’s agricultural department in 1896.

Washington lured the promising young botanist to the Alabama institute with a hefty salary and the promise of two rooms on campus, while most faculty members lived with a roommate. Carver’s special status stemmed from his accomplishments and reputation, as well as his degree from a prominent institution not normally open to Black students.

The agricultural department at Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University) achieved national renown under Carver’s leadership, with a curriculum and a faculty that he helped to shape. Areas of research and training included methods of crop rotation and the development of alternative cash crops for farmers in areas heavily planted with cotton. This work helped under harsh conditions, including the devastation of the boll weevil beginning in 1892.

The development of new crops and diversification of crop uses helped stabilize the livelihoods of American Southerns, including many former enslaved people who had backgrounds similar to Carver’s own. Additionally, the education of African American students at Tuskegee contributed directly to the effort of economic mobilization among Black people.

In addition to formal education in a traditional classroom setting, Carver pioneered a mobile classroom to bring his lessons to farmers. The classroom was known as a “Jesup wagon,” after New York financier and Tuskegee donor Morris Ketchum Jesup.

Carver went on to become a prominent scientific expert and one of the most famous African Americans of his time. Carver achieved international fame in political and professional circles. President Theodore Roosevelt admired his work and sought his advice on agricultural matters affecting the United States. In 1916, Carver became a member of the British Royal Society of Arts—a rare honor for an American. He also advised Indian leader Mahatma Gandhi on matters of agriculture and nutrition.

The educator used his celebrity to promote scientific causes for the remainder of his life. He wrote a syndicated newspaper column and toured the nation, speaking on the importance of agricultural innovation and the achievements at Tuskegee.

What Did George Washington Carver Invent?

Carver’s work at the helm of the Tuskegee Institute’s agricultural department included groundbreaking research on plant biology, much of which focused on the development of new uses for crops including peanuts, sweet potatoes, soybeans, and pecans.

At the time, cotton production was on the decline in the South, and overproduction of a single crop had left many fields exhausted and barren. Carver suggested planting peanuts and soybeans, both of which could restore nitrogen to the soil, along with sweet potatoes. Although these crops grew well in southern climates, there was little demand. Carver’s inventions and research solved this problem and helped struggling sharecroppers in the South find solid ground.

Carver’s inventions include hundreds of products, including more than 300 from peanuts (milk, plastics, paints, dyes, cosmetics, medicinal oils, soap, ink, and wood stains), 118 from sweet potatoes (molasses, postage stamp glue, flour, vinegar, and synthetic rubber), and even a type of gasoline.

Did George Washington Carver Invent Peanut Butter?

Contrary to popular belief, Carver didn’t invent peanut butter. However, he did do a lot of research into new and alternate uses for peanuts.

He even became known as the “Peanut Man” after delivering a speech before the Peanut Growers Association in 1920 attesting to the wide potential of peanuts. The following year, Carver testified before Congress in support of a tariff on imported peanuts, which Congress passed in 1922.

Racial Advocacy and Personal Life

Beyond science, Carver spoke about the possibilities for racial harmony in the United States. From 1923 to 1933, he toured white Southern colleges for the Commission on Interracial Cooperation.

However, Carver largely remained outside of the political sphere and declined to criticize prevailing social norms outright. Thus, the politics of accommodation, which Carver and Booker T. Washington championed, stood in stark contrast to activists who sought more radical change. Nonetheless, Carver’s scholarship and research contributed to improved quality of life for many farming families, making Carver an icon for Black and white Americans alike.

The high-profile scientist developed many friendships throughout his life, including with notable figures like auto magnate Henry Ford. Interested in developing alternatives to gasoline, Ford was drawn to Carver’s work with soybeans and peanuts. They worked on numerous projects together, including a successful replacement for rubber they created in 1942 using the goldenrod plant. Ford even had an elevator installed in Carver’s dormitory so he could access his lab more easily during his later years.

Carver never married and isn’t known to have fathered any children. Often more focused on his work than his relationships, he rejected matchmaking attempts by his friends. Still, around age 40, he began a three-year relationship with Sarah Hunt, a teacher in the Tuskegee Institute night school program. Author Christina Vella suggests in her 2015 biography titled George Washington Carver: A Life that Carver was bisexual.

In 1935, as his health was declining, Carver took on an assistant named Austin W. Curtis. Curtis assisted Carver with his research and writings and even accompanied him while traveling. Curtis also performed some of his own research during this time. “He seems to me more like a son than a person who has just come to work for me,” Carver said of Curtis, who even began calling himself “Baby Carver.”

How Did George Washington Carver Die?

Carver died after falling down the stairs at his home on January 5, 1943, around age 78.

He was buried next to Booker T. Washington on the Tuskegee Institute grounds. Carver’s epitaph reads: “He could have added fortune to fame, but caring for neither, he found happiness and honor in being helpful to the world.” A funeral service for Carver was held at Tuskegee’s chapel.

Legacy: Museum, National Monument, and More

Before Carver’s death, the first museum bearing his named opened in 1941. The George Washington Carver Museum, located on the Tuskegee Institute campus in Alabama, displayed much of his life’s work, including scientific specimens and some of his paintings and drawings. Carver, who had lived a frugal life, helped fund the museum as did his friend and collaborator Henry Ford. The scientist also established the George Washington Carver Foundation at Tuskegee, with the aim of supporting future agricultural research.

In December 1947, a fire broke out in the George Washington Carver museum, destroying much of the collection. One of the surviving works by Carver is a painting of a yucca and a cactus that was displayed at the Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893. Since 1977, the National Park Service has owned and operated the museum.

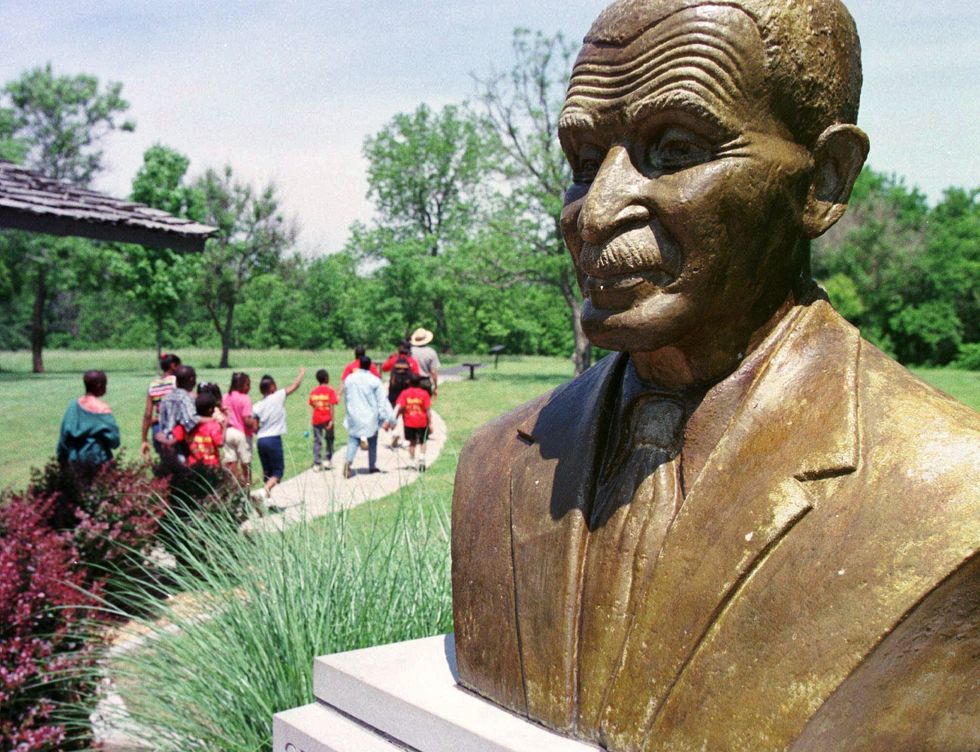

A project to erect a national monument in Carver’s honor also began before his death. Then-Senator Harry S. Truman from Missouri sponsored a bill in favor of a monument during World War II. Supporters of the bill argued that the wartime expenditure was warranted because the monument would promote patriotic fervor among Black Americans and encourage them to enlist in the military. The bill passed unanimously in both houses.

In 1943, President Franklin D. Roosevelt dedicated $30,000 for the George Washington Carver National Monument in Diamond, Missouri, the site of the plantation where Carver lived as a child. It is the first national monument dedicated to an African American. The 210-acre complex includes a statue of Carver as well as a nature trail, museum, and cemetery.

Carver appeared on U.S. commemorative postal stamps in 1948 and 1998, as well as a commemorative half dollar coin minted between 1951 and 1954. Numerous schools bear his name, as do two United States military vessels. In 2005, the Missouri Botanical Garden in St. Louis opened a George Washington Carver Garden, which includes a life-size statue of the garden’s famous namesake.

These honors attest to Carver’s enduring legacy as an icon of African American achievement and of American ingenuity more broadly. Carver’s life has come to symbolize the transformative potential of education, even for those born into the most unfortunate and difficult of circumstances.

Quotes

- It is not the style of clothes one wears, neither the kind of automobile one drives, nor the amount of money one has in the bank, that counts. These mean nothing. It is simply service that measures success.

- When our thoughts—which bring actions—are filled with hate against anyone, Negro or white, we are in a living hell. That is as real as hell will ever be.

- I love to think of nature as an unlimited broadcasting system, through which God speaks to us every hour, if we will only tune in.

- When you can do the common things of life in an uncommon way, you will command the attention of the world.

- Look about you. Take hold of the things that are here. Let them talk to you. You learn to talk to them.

- Fear of something is at the root of hate for others, and hate within will eventually destroy the hater. Keep your thoughts free from hate, and you need have no fear from those who hate you.

- While hate for our fellow man puts us in a living hell, holding good thoughts for them brings us an opposite state of living, one of happiness, success, peace. We are then in heaven.

- Instead of growing morose and despondent over opportunities either real or imaginary that are shut from us, let us rejoice at the many unexplored fields in which there is unlimited fame and fortune to the successful explorer and upon which there is no color line; simply survival of the fittest.

- Our creator is the same and never changes despite the names given Him by people here and in all parts of the world. Even if we gave Him no name at all, He would still be there, within us, waiting to give us good on this earth.

- Nature study is agriculture, and agriculture is nature study—if properly taught.

- More and more as we come closer and closer in touch with nature and its teachings are we able to see the Divine and are therefore fitted to interpret correctly the various languages spoken by all forms of nature about us.

- As I worked on projects which fulfilled a real human need forces were working through me which amazed me. I would often go to sleep with an apparently insoluble problem. When I woke the answer was there.

- We get closer to God as we get more intimately and understandingly acquainted with the things he has created. I know of nothing more inspiring than that of making discoveries for one’s self.

Fact Check: We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn’t look right, contact us!

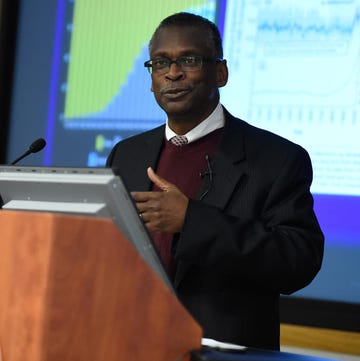

The Biography.com staff is a team of people-obsessed and news-hungry editors with decades of collective experience. We have worked as daily newspaper reporters, major national magazine editors, and as editors-in-chief of regional media publications. Among our ranks are book authors and award-winning journalists. Our staff also works with freelance writers, researchers, and other contributors to produce the smart, compelling profiles and articles you see on our site. To meet the team, visit our About Us page: https://www.biography.com/about/a43602329/about-us

Tyler Piccotti first joined the Biography.com staff as an Associate News Editor in February 2023, and before that worked almost eight years as a newspaper reporter and copy editor. He is a graduate of Syracuse University. When he's not writing and researching his next story, you can find him at the nearest amusement park, catching the latest movie, or cheering on his favorite sports teams.